By the time the wheat paste began to thicken—just right, not too runny, not too stiff—the room at Bolton Elementary had already changed. What began as a lesson plan had become a living process. Paper was torn, not cut. Tape crossed and re-crossed itself like scaffolding. Hands moved with intention. Eyes widened. And in that widening, something essential happened.

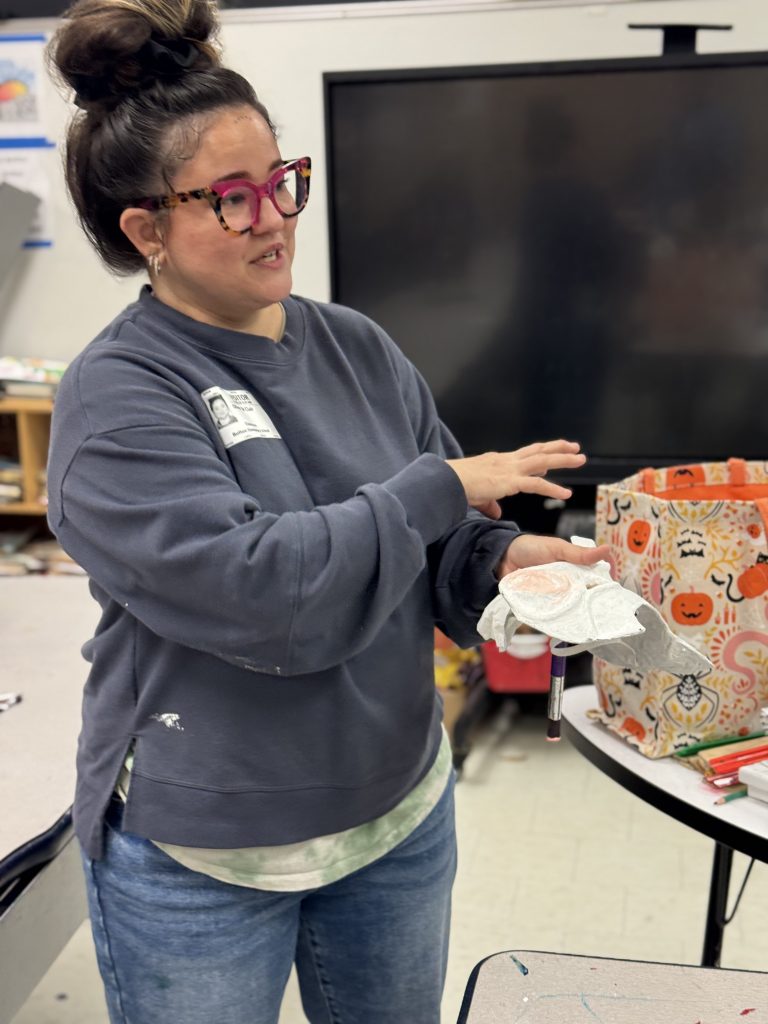

At the center of this transformation was Oliver St. Clair, an artist-teacher whose presence in the classroom is quiet, focused, and deeply observant. Teaching alongside Georgio Sabino, Oliver worked with sixth- and eighth-grade students at Bolton to create papier-mâché masks initially inspired by The Lion King, planned for a March performance. The work, however, did what real art always does—it expanded.

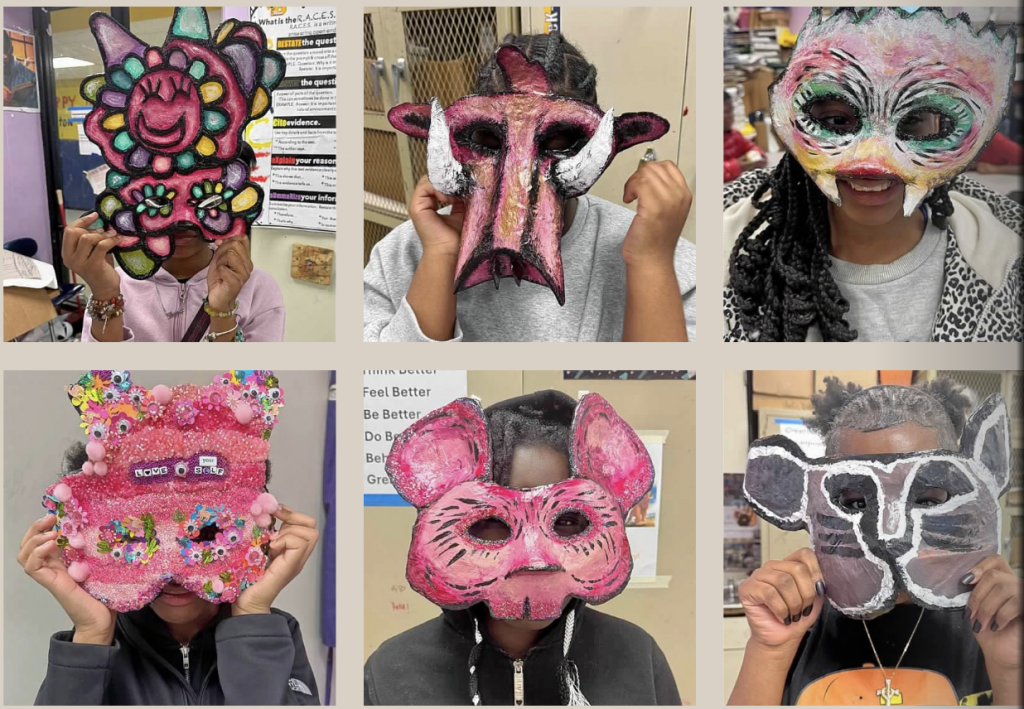

Some students followed the lion’s mane and structure closely. Others felt the pull to branch off, to reshape the form, to invent new colors, new expressions, new identities. Rather than rein them in, Oliver and Mr. Sabino leaned in. She understood that structure and freedom are not opposites—they are partners.

“We’ve been working on this since October,” Sabino reminded the class, grounding the moment in time and discipline. Art, here, was not rushed. It was earned.

Teaching the Process, Not Just the Product

Oliver’s teaching at Bolton focused on process literacy—helping students understand why each step mattered. Construction came first: planning the mask shape, building the armature, learning how balance and symmetry affect form. Then came taping, tearing paper by hand to feel its grain, mixing wheat paste and noticing its chemical change, layering patiently, allowing time to dry. The young scholars has to get use to the feel of wet wheat paste. Can you hear the squeals and ehhh’s.

When Mrs. Oliver was not there, this was science in action. Ratios mattered. So did timing. Math appeared in measurements, proportions, and repetition. Writing entered through reflection—students documenting what worked, what didn’t, and what they would try next.

Oliver moved from table to table, noticing who needed encouragement, who needed challenge, who needed quiet reassurance. She paid attention to detail not only in the artwork, but in the students themselves—the way one hesitated before committing color, the way another worked fearlessly, improvising with embellishments. The gifted artists and the less fortunate; but the less become more each time they came back to the classroom.

“She’s a super hero,” Sabino said, without exaggeration to students. “Highly recommended. Deeply motivated. And she’s in the schools doing the work.”

Watching Art Become Itself

As layers accumulated, so did confidence. Both teachers watched students’ eyes grow larger as the masks began to take shape—flat paper becoming dimensional, imagined ideas becoming tangible objects. Joy appeared not as noise, but as focus. Students asked to stay longer. Cleanup became a negotiation.

Sabino sharpened pencils and gathered written reflections. Oliver passed out scissors and paintbrushes, helping sabino set up water cups, modeling care for tools and space. When it was time to clean, there was reluctance—not because the work was unfinished, but because it mattered.

Each mask told a different story. Some were bold and regal, echoing lions. Others were abstract, emotional, experimental. Every student could explain their choices. Every student could point to a moment where something “went wrong” and became better.

Georgio repeated what he tells all his classes:

“You cannot make a mistake in art—just make it better. Make the mistake part of the process. Don’t get stuck. Keep going.”

Oliver embodied this philosophy. Her own artistic practice—rooted in fiber, paper, symbolism, and vulnerability—translated seamlessly into teaching. Without lecturing, she modeled patience. Without controlling, she guided. She helped students see that art is slow for a reason, and that growth happens in layers.

A Classroom That Remembers

By the end of the session, Bolton Elementary held more than masks. It held evidence of listening, collaboration, and trust. Students had learned how to plan, how to adapt, how to observe change over time. They learned that their ideas mattered—and that discipline makes freedom possible.

Oliver St. Clair did not center herself in the room. She centered the students. And in doing so, she left an imprint far more lasting than papier-mâché: a belief that art is a way of thinking, a way of learning, and a way of becoming.

At Bolton, that belief took shape—slowly, deliberately, beautifully—one torn piece of paper at a time.